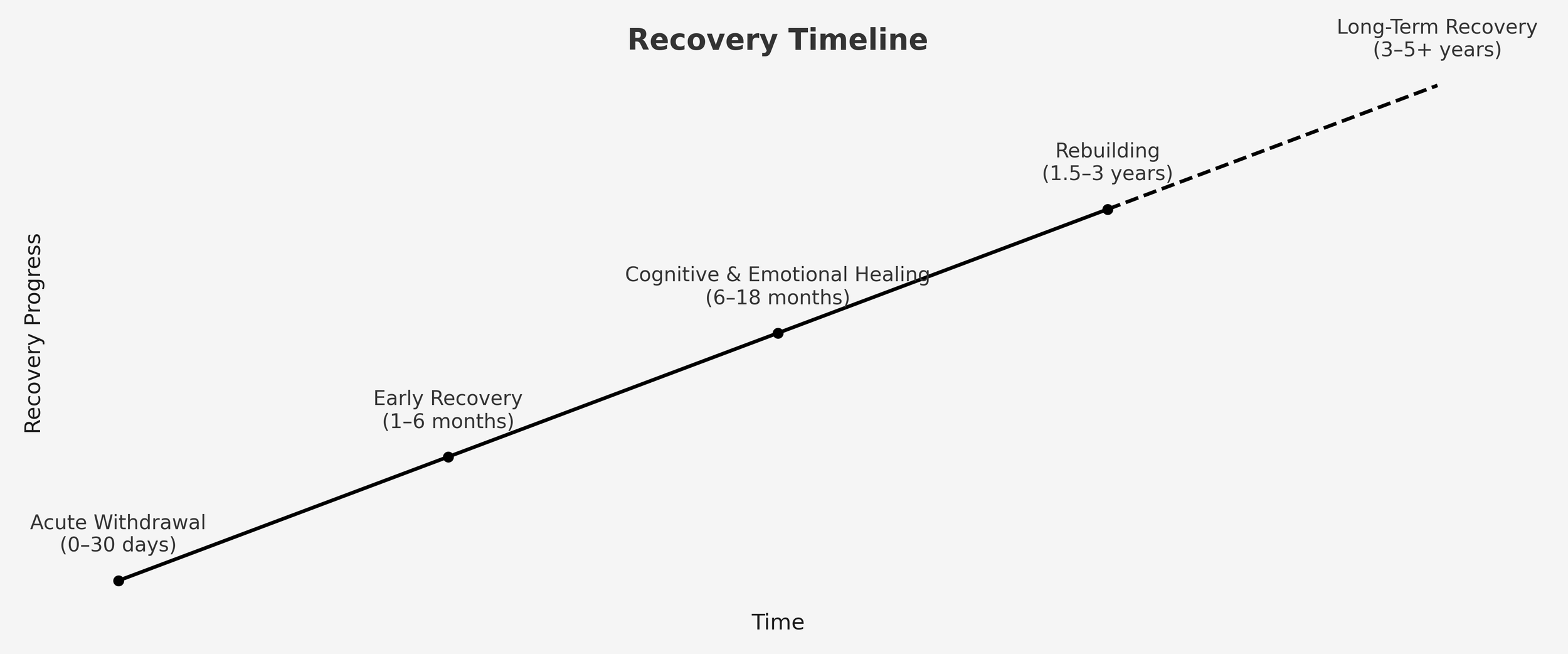

The Recovery Timeline

How Long Does It Really Take to Recover from Meth Addiction?

No one tells you this, but recovery doesn’t start in detox.

It starts the moment you realize your life has become a math problem with no clean solution—and you’re the common denominator.

I used meth for five years. High-functioning, high-achieving, high as hell. Until I wasn’t.

Until everything imploded and the only thing left standing was the question: Can I ever come back from this?

There’s no stopwatch for rebuilding a soul...

“Healing is not becoming the person you were before. It’s letting go of who you imagined yourself to be.”

I was what they call “high-functioning addict.”

What that meant was: no one asked the right questions.

I was editing Olympic broadcasts while high. Writing music. Falling in love. Passing. Smiling. Sinking.

Until everything exploded.

Publicly.

Painfully.

And finally—quietly.

So—How Long Does It Take?

Let’s talk honestly. Not just about detox or abstinence. I’m talking about actual recovery—the slow, granular, gut-wrenching return to yourself.

Here’s the timeline no one gives you, drawn from research, lived experience, and the whispered truths you only hear from those of us who’ve survived it.

Stage 1: Acute Withdrawal (0–30 Days)

Symptoms? Depression. Brain fog. Cravings. Sleep chaos. Emotional numbness so thick it feels like grief in a lead coat.

You’re not crazy. Your brain is simply rebooting after years of dopamine warfare. Methamphetamine floods the reward system with unnatural dopamine spikes, and your brain adapts by downregulating its own production. When the drug stops, so does the flood—and everything feels flat. According to Dr. Nora Volkow, Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and her co-authors (2016), this dopamine crash makes meth one of the hardest drugs to recover from neurologically.

It’s not pretty—but it is progress.

This was the start of something brutal and necessary. Just after detox, in my first weeks of rehab, I landed here — at a quiet cottage in the bush, where silence hit harder than noise ever did.

Stage 2: Early Recovery (1–6 Months)

Your body starts coming back online. Energy flickers. Emotions arrive in technicolor—then crash hard.

This is the “pink cloud” phase. You feel high on hope, you imagine becoming a yoga instructor, a recovery influencer, or a motivational speaker. Then, one Tuesday, your heart slams into a wall, and you cry because your toothbrush feels lonely.

It’s absurd. It’s beautiful. It’s early recovery.

One minute you’re writing affirmations in a notebook called You Got This, and the next you’re wondering if your air fryer resents you. I once spent 40 minutes deciding whether to buy the “superfood” peanut butter or the one that just said “crunchy.” I stood there like I was negotiating peace in the Middle East. That’s what early sobriety does—it turns basic tasks into existential crises.

And yet, this phase brought the first glimpses of possibility. There were moments of clarity, of sudden calm. A walk at dusk. A meal with family. A stupid meme that made me snort with laughter. Each one whispered, “You’re still in here.”

The U.S.-based National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has published research showing that many relapses occur during this phase—not because people are weak, but because the brain hasn’t fully recalibrated yet. It’s running on fumes and fragile optimism.

So if you’re riding that wave—both elated and undone—just know: you’re not failing. You’re healing.

A wide shot of The Dooralong Transformation Centre under a clear blue sky, the place where I spent my early recovery days, surrounded by grace, structure, and strangers who saved me without knowing it.

Stage 3: Cognitive & Emotional Healing (6–18 Months)

Your focus sharpens. You laugh again. And then—out of nowhere—so does the shame.

Around the one-year mark, something strange happens: the emotional backlog hits. Grief. Guilt. Anger. You start remembering the things you tried to forget. You start feeling the weight of who you were—and who you lost.

“Sometimes we carry the past so hard that we forget we survived it.”

This is the marrow of recovery. The place most people quit. Don’t.

Dr. Jean Lud Cadet, a senior neuroscientist and leading expert in stimulant addiction, published research in 2016 specifically on methamphetamine’s long-term impact on the brain. His work shows that emotional regulation, motivation, and executive function can take a year or more to begin normalizing after heavy use.

So if you’re falling apart here—it’s because you’re finally safe enough to feel.

Stage 4: Rebuilding (1.5–3 Years)

Your life starts to shift. You may change careers. Or cities. Or friendships. The pieces don’t go back where they were. They never do. But you begin building something better.

You realize joy isn’t just possible—it’s sustainable. And it doesn’t surprise you anymore.

This is where I’m at. Just past the 18-month mark. Not “healed,” not perfect, but grounded. I’ve begun to notice that the silence in my head is no longer terrifying. I don’t need chaos to feel alive. I still have setbacks, but I also have mornings where I wake up with peace instead of panic. I’m not chasing redemption—I’m constructing a life.

But I’d be lying if I said this part isn’t lonely. There’s a strange grief in getting better—because not everyone comes with you. People you love may not forgive. Or trust. Or even know who you are now. You’re changing while they still remember who you were.

And in that tension, rebuilding can feel like mourning. Mourning the relationships that can’t be salvaged. Mourning your own avoidance. Mourning years you’ll never get back.

Still, I’ve noticed that if I keep showing up—sober, honest, a little more grounded each day—some things do start to grow. They’re smaller than before. Quieter. But they’re real.

And real is enough.

Stage 5: Long-Term Recovery (3–5+ Years)

By now, sobriety isn’t a performance. It’s just the ground you walk on.

Relapse becomes a footnote, not a threat. You stop trying to prove you’re okay. You just are. You’re not fixing anymore—you’re living.

According to research by Rudolf and Bernice Moos, two Stanford University scholars who studied recovery outcomes over decades, people who maintain abstinence for at least three years are far less likely to relapse and report significantly improved life satisfaction—even in the face of setbacks.

But here’s the thing: getting to this point doesn’t mean you’re invincible. It just means you’ve built enough structure to catch yourself when you fall.

You might still flinch at sudden memories. You might still wake up anxious some mornings. But you’ll have tools. You’ll have space. You’ll have history on your side.

More than anything, you’ll have the quiet confidence of someone who’s seen the worst of themselves and still decided to fight for something better.

And that—more than any clean-time milestone—is the victory that matters.

If that sounds long—it is. And that’s okay.

You start feeling better long before you finish the race. At six months, colors return. You find jokes funny again. Music moves you. You stop enduring and start participating.

The Long View

Some of us wore suits to our rock bottoms. Some of us collapsed loudly. Some of us collapsed on mute. It doesn’t matter.

Addiction humbles everyone differently—but recovery asks the same thing from all of us:

Stay.

Feel.

Try again.

There’s no alternate route for the ones who once looked “functional.” No special lane for those who sent invoices while unraveling. In the end, we all rebuild from rubble. We all earn our silence. We all carry things no one else can see.

So how long does it take?

Long enough to stop performing.

Long enough to stop apologizing.

Long enough to live like someone who wants to stay.

And that’s more than enough.

References

Volkow, N.D., Koob, G.F., & McLellan, A.T. (2016). Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(4), 363–371.

→ Volkow is Director of the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse and a leading voice in addiction neuroscience.

Cadet, J.L. (2016). The Clinical Neurobiology of Methamphetamine-Induced Psychosis. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology, 11(3), 448–457.

→ Dr. Cadet is a senior NIH researcher and expert in stimulant addiction and neurotoxicity.

Moos, R.H., & Moos, B.S. (2006). Rates and Predictors of Relapse After Natural and Treated Remission from Alcohol Use Disorders. Addiction, 101(2), 212–222.

→ Longitudinal recovery researchers based at Stanford University with decades of outcome data.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2018). Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (3rd ed.).

→ A gold-standard reference in the field of evidence-based addiction treatment.

Tawwab, N.G. (2021). Set Boundaries, Find Peace: A Guide to Reclaiming Yourself.

→ Tawwab is a licensed therapist and bestselling author focusing on emotional health and boundaries.

Wade, C. (2021). Where to Begin: A Small Book About Your Power to Create Big Change in Our Crazy World.

→ Wade is a poet and activist whose writing centers emotional recovery and resilience.